Welcome to this week’s Math Munch!

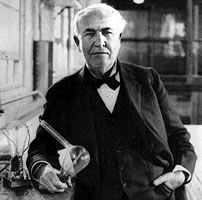

On this day in 1880, Thomas Edison was given a patent for his most famous bright idea—the light bulb.

Edison once said, “Genius is one per cent inspiration, ninety-nine per cent perspiration”—a good reminder that putting in some work is important both in math and in life. He also said, “We don’t know a millionth of one percent about anything.” A humbling thought. Also, based on that quote, it sounds like Edison might have had a use for permilles or even permyraids in addition to percents!

In celebration of this illustrious anniversary, I’d like to share some light mathematical fare relating to, well, light bulbs. For starters, J. Mike Rollins of North Carolina has created each of the Platonic solids inside of light bulbs, ship-in-a-bottle style. Getting just the cube to work took him the better part of twelve hours! Talk about perspiration. Mike has also made a number of lovely Escher-inspired woodcuts. Check ’em out!

Next up is a far-out example from calculus that’s also a good idea for an art project. It’s called the Schwartz lantern. I found out about this amazing object last fall when Evelyn Lamb tweeted and blogged about it.

The big idea of calculus is that we can find exact answers to tough problems by setting up a pattern of approximations that get better and better and then—zoop! take the process to its logical conclusion at infinity. But there’s a catch: you have to be careful about how you set up your pattern!

For example, if you take a cylinder and approximate its surface with a bunch of triangles carefully, you’ll end up with a surface that matches the cylinder in shape and size. But if you go about the process in a different way, you can end up with a surface that stays right near the cylinder but that has infinite area. That’s the Schwartz lantern, first proposed by Karl Hermann Amandus Schwarz of Cauchy-Schwartz fame. The infinite area happens because of all the crinkles that this devilish pattern creates. For some delightful technical details about the lantern’s construction, check out Evelyn’s post and this article by Conan Wu.

Maybe you’ll try folding a Schwartz lantern of your own. There’s a template and instructions on Conan’s blog to get you started. You’ll be glowing when you finish it up—especially if you submit a photo of it to our Readers’ Gallery. Even better, how about a video? You could make the internet’s first Schwartz lantern short film!

At the MOVES Conference last fall, Bruce Torrence of Randolf-Macon College gave a talk about the math of Lights Out. Lights Out is a puzzle—a close relative of Ray Ray—that’s played on a square grid. When you push one of the buttons in the grid it switches on or off, and its neighbors do, too. Bruce and his son Robert created an extension of this puzzle to some non-grid graphs. Here’s an article about their work and here’s an applet on the New York Times website where you can play Lights Out on the Peterson graph, among others. You can even create a Lights Out puzzle of your own! If it’s more your style, you can try a version of the original game called All Out on Miniclip.

There’s a huge collection of Lights Out resources on Jaap’s Puzzle Page (previously), including solution strategies, variations, and some great counting problems. Lights Out and Ray Ray are both examples of what’s called a “sigma-plus game” in the mathematical literature. Just as a bonus, there’s this totally other game called Light Up. I haven’t solved a single puzzle yet, but my limitations shouldn’t stop you from trying. Perspiration!

All this great math work might make you hungry, so…bon appetit!