Welcome to this week’s Math Munch!

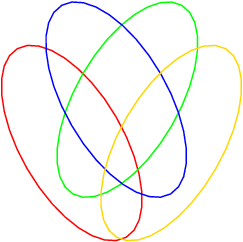

You’ve probably seen Venn diagrams before. They’re a great way of picturing the relationships among different sets of objects.

But I bet you’ve never seen a Venn diagram like this one!

That’s because its discovery was announced only a few weeks ago by Frank Ruskey and Khalegh Mamakani of the University of Victoria in Canada. The Venn diagrams at the top of the post are each made of two circles that carve out three regions—four if you include the outside. Frank and Khalegh’s new diagram is made of eleven curves, all identical and symmetrically arranged. In addition—and this is the new wrinkle—the curves only cross in pairs, not three or more at a time. All together their diagram contains 2047 individual regions—or 2048 (that’s 2^11) if you count the outside.

Frank and Khalegh named this Venn diagram “Newroz”, from the Kurdish word for “new day” or “new sun”. Khalegh was born in Iran and taught at the University of Kurdistan before moving to Canada to pursue his Ph.D. under Frank’s direction.

“Newroz” to those who speak English sounds like “new rose”, and the diagram does have a nice floral look, don’t you think?

When I asked Frank what it was like to discover Newroz, he said, “It was quite exciting when Khalegh told me that he had found Newroz. Other researchers, some of my grad students and I had previously looked for it, and I had even spent some time trying to prove that it didn’t exist!”

Khalegh concurred. “It was quite exciting. When I first ran the program and got the first result in less than a second I didn’t believe it. I checked it many times to make sure that there was no mistake.”

You can click these links to read more of my interviews with Frank and Khalegh.

I enjoyed reading about the discovery of Newroz in these articles at New Scientist and Physics Central. And check out this gallery of images that build up to Newroz’s discovery. Finally, Frank and Khalegh’s original paper—with its wonderful diagrams and descriptions—can be found here.

For even more wonderful images and facts about Venn diagrams, a whole world awaits you at Frank’s Survey of Venn Diagrams.

On Frank’s website you can also find his Amazing Mathematical Object Factory! Frank has created applets that will build combinatorial objects to your specifications. “Combinatorial” here means that there are some discrete pieces that are combined in interesting ways. Want an example of a 5×5 magic square? Done! Want to pose your own pentomino puzzle and see a solution to it? No problem! Check out the rubber ducky it helped me to make!

Finally, Frank mentioned that one of his early mathematical experiences was building hexaflexagons with his father. This led me to browse around for information about these fun objects, and to re-discover the work of Linda van Breemen. Here’s a flexagon video that she made.

And here’s Linda’s page with instructions for how to make one. Online, Linda calls herself dutchpapergirl and has both a website and a YouTube channel. Both are chock-full of intricate and fabulous creations made of paper. Some are origami, while others use scissors and glue.

|

|

|

|

I can’t wait to try making some of these paper miracles myself!

Bon appetit!