Welcome to this week’s Math Munch!

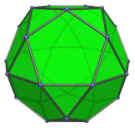

As Justin mentioned last week, the Math Munch team had a blast at the MOVES conference last week. I met so many lovely mathematicians and learned a whole lot of cool math. Let me introduce you to Carolyn Yackel. She’s a math professor at Mercer University in Georgia, and she’s also a mathematical fiber artist who specializes in the beautiful Temari balls you can see below or by clicking the link. Carolyn has exhibited at the Bridges conference, naturally, and her 2012 Bridges page contains an artist statement and some explanation of her art.

|

|

|

Temari is an ancient form of japanese folk art. These embroidered balls feature various spherical symmetries, and part of Carolyn’s work has been figure out how to create and exploit these symmetries on the sphere. I mean how do you actually make it that symmetric? Can you see in the pictures above how the symmetry of the Temari balls mimic the Archimedean solids? Carolyn has even written about using Temari to teach mathematics, some of which you can read here, if you like.

Read Carolyn Yackel’s Q&A with Math Munch.

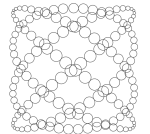

Up next, you may remember Edmund Harriss from this post, and you might recall Desmos from this post. Well the two have come together! On his blog, Maxwell’s Demon, Edmund shared a whole bunch of interactive graphs from Desmos, in a post he called “Form Follows Function.” Click on the link to read the article, and click on the images to get graphs full of sliders you can move to alter the images. In fact, you can even alter the equations that generate them, so dig in, play some, and see what you can figure out.

|

|

|

Finally, I want to share a piece of music I really love. “Clapping Music” was written by Steve Reich in 1972. It is considered minimalist music, perhaps because it features two performers doing nothing but clapping. If you watch this performance of “Clapping Music” first (and I suggest you do) it might just sound like a bunch of jumbled clapping. But the clapping is actually built out of some very simple and lovely mathematical patterns. Watch the video below and you’ll see what I mean.

Did you see the symmetries in the video? I noticed that even though the pattern shifts, it’s always the same backwards as forwards. And I also noticed that the whole piece is kind of the same forwards and backwards, because of the way that the pattern lines back up with itself. Watch again and see if you get what I mean.

Bonus: Math teacher, Greg Hitt tweeted me about “Clapping Music” and shared this amazing performance by six bounce jugglers!!! It’s cool how you can really see the patterns in the live performance.

I hope you find something you love and dig in. Bon appetit!