Welcome to this week’s Math Munch!

There’s been a lot of fuss recently about the Mayan calendar and the “end of the world.” You’ll be relieved to hear that the world continues to hang in there. In fact, no less an authority than NASA put out a video to help clear up the misinformation surrounding the rolling over of the Mayan calendar.

All of the doomsday talk did get me researching the Mayan calendar and number system. Check out this page that discusses Mayan numerals and will even count and skip-count for you. Once you’ve got the knack of how to count in the Mayan system, maybe you’ll want to try to decipher the numbers on a Mayan ballcourt marker in this interactive applet.

All of the doomsday talk did get me researching the Mayan calendar and number system. Check out this page that discusses Mayan numerals and will even count and skip-count for you. Once you’ve got the knack of how to count in the Mayan system, maybe you’ll want to try to decipher the numbers on a Mayan ballcourt marker in this interactive applet.

A cool fact that I learned from that first page is that the Mayans also had another and fancier way of writing down numbers: face glyphs. I found a really comprehensive article by Mark Pitts that describes both face glyphs and the ordinary system, too.

The Mayan face glyphs for 0, 1, 2, and 3:

mih, jun, cha’, and ux.

There are many interesting kinds of calendars that human being have developed over the centuries, all with different styles, different mathematical patterns, and different connections to the natural and human worlds. We’ve featured the Cloctal before, but how about some links to some other fun mathy calendars as the new year approaches?

I’m always amazed by what the internet produces when I dream up a search term like “binary calendar.” Perhaps you’ve seen a binary clock before—if not, check out this one—but I was delighted to find several different takes on a binary calendar served up by Google. Juan Osborne designed a binary calendar with all of the dates written out it a big colorful loop. Next, can you figure out the secret to this wooden binary calendar by Ken and Bobbie Ralphs? (It’s a lot like a marble calculator.) And third, here’s a binary calendar that you can make using just twelve pennies, courtesy of exploringbinary.com!

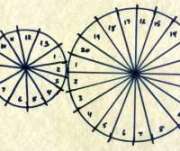

The Aztec tonalpohualli calendar.

There are many more amazing calendars to explore. Maybe you’ll check out Aztec calendar wheels, or find out about anniversaries of mathematicians from this calendar. (Isaac Newton was born on Christmas!) There are even more great calendars to explore at the Calendar Wiki, including some new calendars that have been proposed to “fix” our calendar—the Gregorian calendar—to get rid of traits like uneven months and leap years.

Speaking of anniversaries, this past Saturday was the 125th anniversary of the birth of the great Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. Google celebrated the occasion with this doodle on the Indian Google homepage.

Speaking of anniversaries, this past Saturday was the 125th anniversary of the birth of the great Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. Google celebrated the occasion with this doodle on the Indian Google homepage.

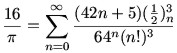

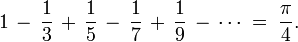

Ramanujan’s story is inspiring and also in some ways tragic. There’s plenty of information about Ramanujan on the web, but you might particularly enjoy reading this recent tribute to him by Dilip D’Souza. One surprising fact I ran across is that one of Ramanujan’s formulas involving pi appeared in (of all places) the movie High School Musical.

Ramanujan’s 125th birthday this year became the occasion for India’s first National Mathematics Day. What a cool holiday! Here is a clip from Indian television that shows some Indian students honoring Ramanujan and doing some math.

I can’t understand everything that’s happening in the video, but it’s simply amazing to catch a glimpse of students on the other side of the world being excited about math. Also, you might notice that some of the students are figuring out cube roots of large numbers, while some others are shown figuring out what day of the week certain dates fell on. That’s a neat calendar-related feat that you can read more about here.

And just because it made me giggle, here’s a little bonus video.

Bon appetit!