Welcome to this week’s Math Munch!

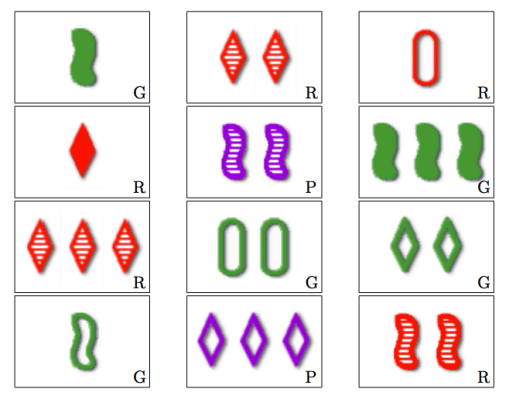

To set up the punchline: if you haven’t played the card game SET before, do yourself a favor and go try it out now!

(Or if you prefer, here’s a video tutorial.)

(And even if you have played before, go ahead and indulge yourself with a round. You deserve a SET break. 🙂 )

Now, we’ve shared about SET before, but recently there has been some very big SET-related news. Although things have been quieter around Georgia Tech since summer has started, there has been a buzz both here and around the internet about a big breakthrough by Vsevolod Lev, Péter Pál Pach, and Georgia Tech professor Ernie Croot. Together they have discovered a new approach to estimate how big a SET-less collection of SET cards can be.

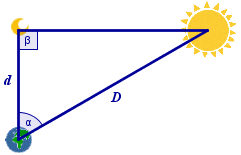

In SET there are a total of 81 cards, since each card expresses one combination of four different characteristics (shape, color, filling, number) for which there are three possibilities each. That makes 3^4=81 combinations of characteristics. Of these 81 cards, what do you think is the most cards we could lay out without a SET appearing? This is not an easy problem, but it turns out the answer is 20. An even harder problem, though, is asking the same question but for bigger decks where there are five or ten or seventy characteristics—and so 3^5 or 3^10 or 3^70 cards. Finding the exact answer to these larger problems would be very, very hard, and so it would be nice if we could at least estimate how big of a collection of SET-less cards we could make in each case. This is called the cap set problem, and Vsevolod, Péter, and Ernie found a much, much better way to estimate the answers than what was previously known.

To find out more on the background of the cap set problem, check out this “low threshold, high ceiling” article by Michigan grad student Charlotte Chan. And I definitely encourage you to check out this article by Erica Klarreich in Quanta Magazine for more details about the breakthrough and for reactions from the mathematical community. Here’s a choice quote:

Now, however, mathematicians have solved the cap set problem using an entirely different method — and in only a few pages of fairly elementary mathematics. “One of the delightful aspects of the whole story to me is that I could just sit down, and in half an hour I had understood the proof,” Gowers said.

(For further wonderful math articles, you’ll want to visit Erica’s website.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

These are photos of Vsevolod, Péter, Ernie, Charlotte, Erica, and the creator of SET, geneticist Marsha Jean Falco.

Ready for more? Earlier this week, I ran across this animation:

It shows two ways of modeling the motions of the sun and the planets in the sky. On the left is a heliocentric model, which means the sun is at the center. On the right is a geocentric model, which means the earth is at the center.

Around 250 BC, Aristarchus calculated the size of the sun, and decided it was too big to revolve around the earth!

Now, I’m sure you’ve heard that the sun is at the center of the solar system, and that the earth and the planets revolve around the sun. (After all, we call it a “solar system”, don’t we?) But it took a long time for human beings to decide that this is so.

I have to confess: I have a soft spot for the geocentric model. I ran across the animation in a Facebook group of some graduates of St. John’s College, where I studied as an undergrad. We spent a semester or so reading Ptolemy’s Almagest—literally, the “Great Work”—on the geocentric model of the heavens. It is an incredible work of mathematics and of natural science. Ptolemy calculated the most accurate table of chords—a variation on a table of the sine function—that existed in his time and also proved intricate facts about circular motion. For example, here’s a video that shows that the eccentric and epicyclic models of solar motion are equivalent. What’s really remarkable is that not only does Ptolemy’s system account for the motions of the heavenly bodies, it actually gave better predictions of the locations of the planets than Copernicus’s heliocentric system when the latter first debuted in the 1500s. Not bad for something that was “wrong”!

Here are Ptolemy and Copernicus’s ways of explaining how Mars appears to move in the sky:

|

|

Maybe you would like to learn more about the history of models of the cosmos? Or maybe you would like tinker with a world-system of your own? You might notice that the circles-on-circles of Ptolemy’s model are just like a spirograph or a roulette. I wonder what would happen if we made the orbit circles in much different proportions?

Now, I was very glad to take this stroll down memory lane back to my college studies, but little did I know that I was taking a second stroll as well: the person who created this great animation, I had run across several other pieces of her work before! Her name is Malin Christersson and she’s a PhD student in math education in Sweden. She is also a computer scientist who previously taught high school and also teaches many people about creating math in GeoGebra. You can try out her many GeoGebra applets here. Malin also has a Tumblr where she posts gifs from the applets she creates.

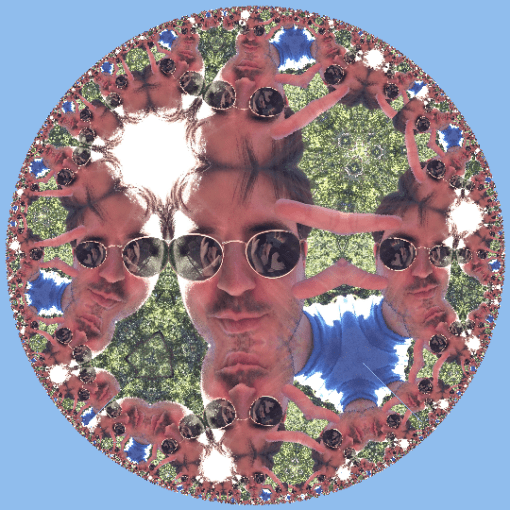

About a year ago I happened across an applet that lets you create art in the style of artist (and superellipse creator) Piet Mondrian. But it also inverts your art—reflects it across a circle—so that you can view your own work from a totally different perspective. Then just a few months later I delighted in finding another applet where you can tile the hyperbolic plane with an image of your choice. (I used one tiling I produced as my Twitter photo for a while.)

And now come to find out these were both made by Malin, just like the astronomy animation above! And Malin doesn’t stop there, no, no. You should see her fractal applets depicting Julia sets. And her Rolling Hypocycloids and Epicycloids are can’t-miss. (Echoes of Ptolemy there, yes?!)

And please don’t miss out on Malin’s porfolio of applets made in the programming language Processing.

It’s a good feeling to finally put the pieces together and to have a new mathematician, artist, and teacher who inspires me!

I hope you’ll find some inspiration, too. Bon appetit!

A

A