Welcome to this week’s Math Munch! This week, I’m sharing with you some math things that make me go, “What?!” Maybe you’ll find them surprising, too.

The first time I heard about this I didn’t believe it. If you’ve never heard it, you probably won’t believe it either.

Ever tried to solve one of these? I’ve only solved a Rubik’s cube once or twice, always with lots of help – but every time I’ve worked on one, it’s taken FOREVER to make any progress. Lots of time, lots of moves…. There are 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 (yes, that’s 43 quintillion) different configurations of a Rubik’s cube, so solving a cube from any one of these states must take a ridiculous number of moves. Right?

Ever tried to solve one of these? I’ve only solved a Rubik’s cube once or twice, always with lots of help – but every time I’ve worked on one, it’s taken FOREVER to make any progress. Lots of time, lots of moves…. There are 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 (yes, that’s 43 quintillion) different configurations of a Rubik’s cube, so solving a cube from any one of these states must take a ridiculous number of moves. Right?

Nope. In 2010, some mathematicians and computer scientists proved that every single Rubik’s cube – no matter how it’s mixed up – can be solved in at most 20 moves. Because only an all-knowing being could figure out how to solve any Rubik’s cube in 20 moves or less, the mathematicians called this number God’s Number.

Once you get over the disbelief that any of the 43 quintillion cube configurations can be solved in less than 20 moves, you may start to wonder how someone proved that. Maybe the mathematicians found a really clever way that didn’t involve solving every cube?

Not really – they just used a REALLY POWERFUL computer. Check out this great video from Numberphile about God’s number to learn more:

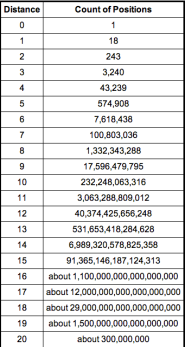

Here’s a chart that shows how many Rubik’s cube configurations need different numbers of moves to solve. I think it’s surprising that so few required all 20 moves. Even though every cube can be solved in 20 or less moves, this is very hard to do. I think it’s interesting how in the video, one of the people interviewed points out that solving a cube in very few moves is probably much more impressive than solving a cube in very little time. Just think – it takes so much thought to figure out how to solve a Rubik’s cube at all. If you also tried to solve it efficiently… that would really be a puzzle.

Next, check out this cool video. Its appealing title is, “How to create chocolate out of nothing.”

This type of puzzle, where area seems to magically appear or disappear when it shouldn’t, is called a geometric vanish. We’ve been talking about these a lot at school, and one of the things we’re wondering is whether you can do what the guy in the video did again, to make a second magical square of chocolate. What do you think?

Finally, I’ve always found infinity baffling. It’s so hard to think about. Here’s a particularly baffling question: which is bigger, infinity or infinity plus one? Is there something bigger than infinity?

Finally, I’ve always found infinity baffling. It’s so hard to think about. Here’s a particularly baffling question: which is bigger, infinity or infinity plus one? Is there something bigger than infinity?

I found this great story that helps me think about different sizes of infinity. It’s based on similar story by mathematician Raymond Smullyan. In the story, you are trapped by the devil until you guess the devil’s number. The story tells you how to guarantee that you’ll guess the devil’s number depending on what sets of numbers the devil chooses from.

I found this great story that helps me think about different sizes of infinity. It’s based on similar story by mathematician Raymond Smullyan. In the story, you are trapped by the devil until you guess the devil’s number. The story tells you how to guarantee that you’ll guess the devil’s number depending on what sets of numbers the devil chooses from.

Surprisingly, you’ll be able to guess the devil’s number even if he picks from a set of numbers with an infinite number of numbers in it! You’ll guess his number if he picked from the counting numbers larger than zero, positive or negative counting numbers, or all fractions and counting numbers. You’d think that there would be too many fractions for you to guess the devil’s number if he included those in his set. There are infinitely many counting numbers – but aren’t there even more fractions? The story tells you about a great way to organize your guessing that works even with fractions. (And shows that the set of numbers with fractions AND counting numbers is the same size as the set of numbers with just counting numbers… Whoa.)

Is there something mathematical that makes you go, “What?!” How about, “HUH?!” If so, send us an email or leave us a note in the comments. We’d love to hear about it!

Bon appetit!