Welcome to this week’s Math Munch!

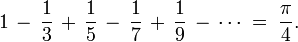

We’ve posted a lot about pi on Math Munch – because it’s such a mathematically fascinating little number. But here’s something remarkable about pi that we haven’t yet talked about. Did you know that pi is equal to four times this?

Yup. If you were to add and subtract fractions like this, for ever and ever, you’d get pi divided by 4. This remarkable fact was uncovered by the great mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who is most famous for developing the calculus. Check out this interactive demonstration from the Wolfram Demonstrations Project to see how adding more and more terms moves the sum closer to pi divided by four. (We’ve written about Wolfram before.)

Yup. If you were to add and subtract fractions like this, for ever and ever, you’d get pi divided by 4. This remarkable fact was uncovered by the great mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who is most famous for developing the calculus. Check out this interactive demonstration from the Wolfram Demonstrations Project to see how adding more and more terms moves the sum closer to pi divided by four. (We’ve written about Wolfram before.)

I think this is amazing for a couple of reasons. First of all, how can an infinite number of numbers add together to make something that isn’t infinite??? Infinitely long sums, or series, that add to a finite number have a special name in mathematics: convergent series. Another famous convergent series is this one:

The second reason why I think this sum is amazing is that it adds to pi divided by four. Pi is an irrational number – meaning it cannot be written as a fraction, with whole numbers in the numerator and denominator. And yet, it’s the sum of an infinite number of rational numbers.

In this video, mathematician Keith Devlin talks about this amazing series and a group of mathematical musicians (or mathemusicians) puts the mathematics to music.

This video is part of a larger work called Harmonious Equations written by Keith and the vocal group Zambra. Watch the rest of them, if you have the chance – they’re both interesting and beautiful.

Next up, Conway’s Game of Life is a cellular automaton created by mathematician John Conway. (It’s pretty fun: check out this to download the game, and this Munch where we introduce it.) It’s discrete – each little unit of life is represented by a tiny square. What if the rules that determine whether a new cell is formed or the cell dies were applied to a continuous domain? Then, it would look like this:

Looks like a bunch of cells under a microscope, doesn’t it? Well, it’s also a cellular automaton, devised by mathematician Stephan Rafler from Nurnberg, Germany. In this paper, Stephan describes the mathematics behind the model. If you’re curious about how it works, check out these slides that compare the new continuous version to Conway’s model.

Finally, I just got a pumpkin. What should I carve in it? I spent some time browsing the web for great mathematical pumpkin carvings. Here’s what I found.

I’d love to hear any suggestions you have for how I should make my own mathematical pumpkin carving! And, if you carve a pumpkin in a cool math-y way, send a picture over to MathMunchTeam@gmail.com!

Bon appetit!