Welcome to this week’s Math Munch!

What is 3 x 4? 3 x 4 is 12.

Well, yes. That’s true. But something that’s wonderful about mathematics is that seemingly simple objects and problems can contain immense and surprising wonders.

As I’ve mentioned before, the part of mathematics that works on counting problems is called combinatorics. Here are a few examples for you to chew on: How many ways can you scramble up the letters of SILENT? (LISTEN?) How many ways can you place two rooks on a chessboard so that they don’t attack each other? And how many squares can you count in a 3×4 grid?

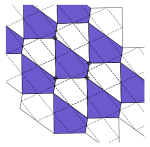

Here’s one combinatorics problem that I ran across a while ago that results in some wonderful images. Instead of asking about squares in a 3×4 grid, a team at the Dubberly Design Office in San Francisco investigated the question: how many of ways can a 3×4 grid can be partitioned—or broken up—into rectangles? Here are a few examples:

|

|

|

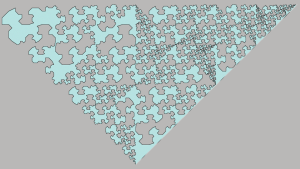

How many different ways to do this do you think there are? Here’s the poster that they designed to show the answer that they found! You can also check out this video of their solution.

How many different ways to do this do you think there are? Here’s the poster that they designed to show the answer that they found! You can also check out this video of their solution.

In their explanation of their project, the team states that “Design tools are becoming more computation-based; designers are working more closely with programmers; and designers are taking up programming.” Designing the layout of a magazine or website requires both structural and creative thinking. It’s useful to have an idea of what all the possible layouts are so that you can pick just the right one—and math can help you to do it!

If you’d like to try creating a few 3×4 rectangle partitions of your own, you can check out www.3x4grid.com. [Sadly, this page no longer works. See an archive of it here. -JL, 10/2016]

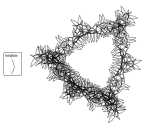

Next up, explosions! I could tell you about the math of the game Minesweeper (you can play it here), or about exploding dice. But the kind of explosion I want to share with you today is what’s called a “combinatorial explosion.” Sometimes a problem that appears to be an only slightly harder variation of an easy problem turns out to be way, way harder. Just how BIG and complicated even simple combinatorics problems can get is the subject of this compelling and also somewhat haunting video.

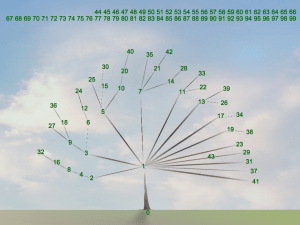

Finally, all of this counting got me thinking about big numbers. Previously we’ve linked to Math Cats, and Wendy has a page where you can learn how to say some really big numbers. But thinking about counting also made me remember an experience I had in middle school where I found out just how big numbers could be! I was in seventh grade when I read this article from the December 1995 issue of Discover Magazine. It’s called “Infinity Plus One, and Other Surreal Numbers” and was written by Polly Shulman. I remember my mind being blown by all of the talk of infinitely-spined aliens and up-arrow notation for naming numbers. Here’s an excerpt:

“Mathematicians and precocious five-year-olds have long been fascinated by the endlessness of numbers, and they’ve named the endlessness infinity. Infinity isn’t a number like 1, 2, or 3; it’s hard to say what it is, exactly. It’s even harder to imagine what would happen if you tried to manipulate it using the arithmetic operations that work on numbers. For example, what if you divide it in half? What if you multiply it by 2? Is 1 plus infinity greater than, less than, or the same size as infinity plus 1? What happens if you subtract 1 from it?”

After I read this article, John Conway and Donald Knuth became heros of mine. (In college, I had the amazing fortune to have breakfast with Conway one day when he was visiting to give a lecture!) Knuth has a book about surreals that’s the friendliest introduction to the surreal numbers that I know of, and in this video, Vi Hart briefly touches on surreal numbers in discussing proofs that .9 = 1. Boy, would I love to see a great video or online resource that simply and beautifully lays out the surreal numbers in all their glory!

It was fun for me to remember that Discover article. I hope that you, too, run across some mathematics that leaves a seventeen-year impression on you!

Bon appetit!